Part II

In the 1970s, Lexington, Kentucky had a wealth class that coexisted with the rest of us normies. Even at my junior high school, judging eyeballs would scan our shoes, then the logos on our shirts, and eventually the car driven by our parents. Ours was a 1974 Fiat hatchback purchased while living in Europe on academic sabbatical. It served our family for years afterward, even though it lacked air conditioning and still reeked of vinyl cooked by a cross-country trip through the Salt Flats of Utah.

Since I was “still cooking” myself, so to speak, clothing purchases were kept at a minimum. I was reminded that it was wasteful to spend too much on that which I’d just outgrow anyway. Needless to say, any dreams I had of owning a pastel golf shirt with an alligator on the chest would require my own initiative, which meant I mostly wore knock-offs from the local McAlpin’s.

We could always manage a record, though. Most cost between four and six dollars, slightly more than the price of a movie and certainly longer lasting. Fifty years later, I still own many of those LPs.

But record purchases, like clothing, were also judged. At first it was easy to conform. Fleetwood Mac had dropped Rumors and everyone was singing “Thunder only happens when it’s raining…”. When the Eagles unleashed Hotel California, we knew every word and even spun up our own stories about that dreaded establishment with its “Steely Knife.” But then I bought Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life and it was bye, bye Glenn Frey. I loved every single track and, wanting more, began exploring similar albums. On this, my best friend Sean and I agreed. The rest of our peers parted ways over such pursuits.

Soon I would part ways with the entire town. In 1980 my family left the green acres of Kentucky for the shockingly ugly weed grass of Houston. It was a climate filled with flying brown bugs and worse yet, a neighborhood with no kids my age. Or maybe that was a blessing. For the remainder of my high school years, I spent most of my time alone in a converted attic bedroom, my face pressed to an electric fan. Then the cable era dawned and with it I became a child of MTV. My tastes pivoted to a weird mix of new wave, soul and what we now call Yacht Rock. I loved Toto and The Cars in equal measure. And I wore out Thriller, especially those last three songs (Human Nature, P.Y.T, and The Lady In My Life). I often tore the synth ads from Keyboard magazine and taped them over my bed. These were the keyboards I saw on MTV and Soul Train, the ones I could never afford — $4000 for a Prophet-5? That’s 1981 dollars: might as well pine for a Ferrari too.

Lexington became a fuzzy memory because the future was now. I mostly remembered clinging to a disdain for arena rock and, specifically, the California sound so keenly associated with growing up there.

***

Decades later, I feel weirdly drawn back to this previously-maligned California sound. Maybe things changed a bit upon learning that a 16-year-old Jackson Browne had written Nico’s “These Days.” He also did the track’s intricate guitar picking, which adds buoyancy to her laconic vocals. This led to an exploration of Browne classics like The Pretender and For Everyman.

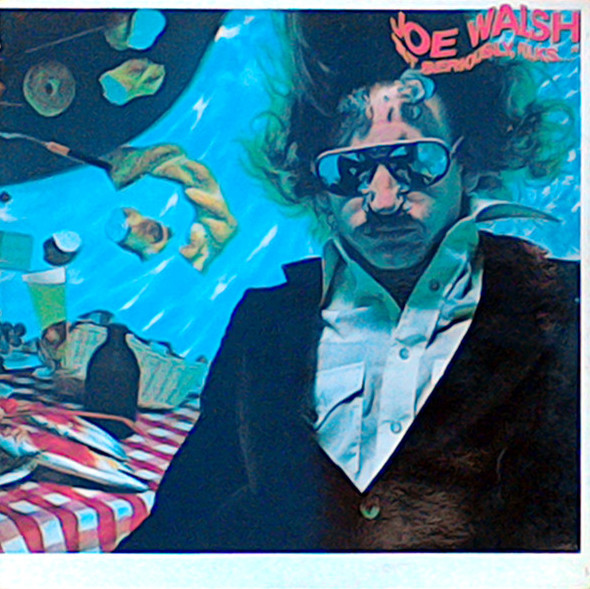

Then there’s Joe Walsh. His early output including classics from The James Gang and Barnstorm all showcase his exceptional songwriting talent. And yet for years I associated him with the dipshit rich kids who inhabited my world, those entitled deviants who puffed low-grade dirt weed while dancing around to “Life’s Been Good To Me.” I have since realized that you can sometimes forgive a song if you play the entire record. In the case of But Seriously, Folks, tunes like “Tomorrow” and “Indian Summer” prove that point.

A band like Little Feat also seems more palatable now. After all, Lowell George was the father of Inara George, one half of the genius pop duo The Bird and The Bee. Jackson Browne wrote “Of Missing Persons” in her honor when Lowell died of a drug-related heart attack at age 34. Inara was only five then. I saw Jackson Browne perform this song on the Hold Out tour my first year in Houston, thanks to a nice neighbor who took me to see him. I’ll never forget the crowd’s reaction to him singing the line, “They’re walking slow in Houston…”

***